A Fenwick alumna’s post-Mother’s Day reflection on how being a good neighbor means loving your neighbor as yourself.

By Quiwana Reed Bell ’96

I was born the snowy winter of 1979 in Maywood, Illinois, to Jacqueline and Ronald Reed. My father, Ronnie, was born and raised a tough bi-racial kid from the west side of Chicago, near Pulaski and Roosevelt. My father never knew his mother.

My mother, Jackie, was born and raised in 1950 Natchez, Mississippi — a famous plantation town near the ports where slave-produced cotton and sugar cane was once exported. She is the oldest of seven children and grew up on family-owned land that also included homes for her grandparents (both paternal and maternal), aunts, uncles, cousins and neighbors, who were like family. Her father, Oliver, was a handyman and janitor with a stuttering problem and a heart of gold; and her mother, Josephine, was a stern yet dignified seamstress who also worked for more than 20 years at the pecan factory. Her family of nine lived in a two-bedroom/one-bathroom house. They went to church on Sundays. They socialized and cared for each other. They didn’t have much but never felt poor. They were a community. And they were happy.

My mother left Mississippi after high school, after having a child out of wedlock with a man who was unwilling to marry. She came to Chicago in the summer of 1969 to visit her Aunt Mavis, her dad’s older sister. She lived on 13th and Pulaski in a brick two-flat building on the west side of Chicago. Aunt Mavis had 10 children of her own with her entrepreneur husband Ed, who ran an auto mechanic shop. Although they owned the entire building, they lived in only one of the units which had two bedrooms, one bathroom and a back sun porch. Ten kids, two parents and now visiting cousin Jackie from Mississippi all in one unit. The block was lively. People sat on their stoops in the evenings for entertainment. The kids would play loudly up and down the streets. Neighbors knew each other; supported each other; fought and gossiped about each other. It was a family. A community. And they were happy.

During her summer-time visit, Jackie met Ronnie, who was a friend of her cousin Roger. They quickly fell in love and married only three months after meeting on February 14, 1970. Jackie never returned to Mississippi to live. In Mississippi still was her infant son, Derek. He had stayed with her family while she traveled to Chicago. This was not a big deal. The family was seen as a unit. Jackie’s son Derek was not her property, but a member of a larger family unit where everyone contributes, supports and belongs.

Sharing brings happiness

This was a sentiment taught to my mother very early on in her childhood. She was born in segregated Mississippi where black people were still forced to live separately. This separation, however, was not all bad. Black communities had viable businesses — bakeries, dentist offices and insurance companies. It was a community where people looked out for one another. I would often hear stories of how if one person on the block killed a cow, then everyone on the block would have meat. Similarly, during my summers that I spent in Natchez, MS, I would often hear my grandmother say, “Go run this pot of greens that I picked and cooked over to Ms. ‘So and So’s house.” It was natural to share. It was natural to help others. It brought happiness. My mom never felt poor. She didn’t have a lot of fear and anxiety. Her family lived in peace. Even amid all the stuff going on in the world — they were shielded in “their community.”

Black folks have always had to be communal with each other in America in order to survive:

- We had to help each other as we were packed like cargo at the bottom of slave ships.

- We had to help each other as we sang songs together in the long days in the hot cotton fields in Mississippi.

- We had to help each other as we navigated our way through lynching and rape and beatings.

- We had to support each other in demonstrations and boycotts fighting for equal rights.

- We had to support each other through redlining/housing and employment discrimination.

Today we still have to support each other through families being ripped apart as a result of mass incarceration, disinvestment of neighborhood schools and economic opportunity, and the resulting crime that plagues our communities.

Continue reading “A Mother’s Legacy of Caring”

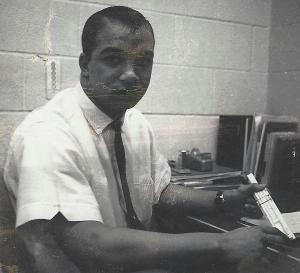

School records dating back 64 years confirm that alumnus Richard Cochrane ’59 blazed a trail as Fenwick’s very first African-American student and graduate. Originally from Maywood, IL, Mr. Cochrane now lives in the sunny Southwest. In high school, he was active in student government (class treasurer and secretary) and played football and basketball (captain).

School records dating back 64 years confirm that alumnus Richard Cochrane ’59 blazed a trail as Fenwick’s very first African-American student and graduate. Originally from Maywood, IL, Mr. Cochrane now lives in the sunny Southwest. In high school, he was active in student government (class treasurer and secretary) and played football and basketball (captain).